“Shifting political signs” on coal point to an uncertain future; plus: fresh statistics on China energy and climate

Despite China’s dual-carbon (shuang tan) goals, and predictions of an “inevitable trend” of decline, 2021 was a good year for coal.

Last year, China recorded its “biggest increase” in total energy consumption (+5.2% year-on-year) in a decade. Total electricity consumption has doubled compared to 2010 (Scroll down for more newly published 2021 statistics).

To meet the surging demand, China produced 5.7% more coal and imported 6.6% more from external suppliers compared to 2020.

This led to record-high coal consumption (+4.6%) and coal power generation, pushing the average utilization hours of coal-fired power units up by 6%.

But that wasn’t enough. Energy shortages affected swaths of China in 2021. They intensified in August when more than 20 provinces curbed energy and power consumption for both industry and residents. Energy-intensive industries such as steel, cement, and aluminum across China were forced to shut down or lower production, resulting in soaring commodity prices.

Analysts said an imbalance in China’s coal sector was the main cause. In short, as coal prices soared but power tariffs remained stable, power plants lost money for every lump of coal they turned into electricity. They had no incentive to increase production.

The soaring coal prices made coal mining the third-most profitable industry in 2021, with companies above a certain size growing their revenue (+58.3%) and profit (+221.7%). Coal power generators, on the other hand, had a much colder winter. According to Chen Zongfa, director of China Energy Research Society, the annual losses of coal power plants reached 300 billion yuan.

With strong state regulation, the shortages started to ease by the end of October. In 2022, the central government continues prioritizing energy security, pressuring coal power plants to “release their full potential” and “improve output to the fullest” despite the industry-wide high debt levels and unprofitability. (See last week’s newsletter.)

Moreover, in recent days, political instructions and various government documents have outlined supportive policies to boost coal production, transportation, and storage, underlining that coal will remain the dominant energy source in the years to come.

The recent announcements seek to ensure 2021’s shortages won’t reoccur. These policies place “securing coal supply” and “stabilizing coal prices” at the center of energy security. But as a consequence, this points to a very uncertain future for China’s decarbonization.

“Shifting political signals”

More coal-fired power plants are coming. A study published last week concludes 33 gigawatts (GW) of coal power capacity entered construction in 2021, the “most since 2016.”

The study, compiled by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air(CREA) and Global Energy Monitor (GEM), also found China unfroze the approval of new coal projects and cleared five projects totaling 7.3GW in “just the first six weeks” of 2022, which, the authors consider as “shifting political signals.”

Ten days ago, China’s state planner, the National Reform and Development Commission (NDRC), also approved three new large-scale coal mining projects in Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia, totaling 19 megatonnes (Mt) of yearly coal mining capacity, in the name of “securing stable energy supply and optimizing coal industry structure.”

According to an incomplete list of planned projects published last week, during the 14th five-year plan (14FYP, 2021-2025), China plans to add 28GW of coal power generation capacity to existing plants and retrofit 42GW coal power capacity as “matching facilities” that should improve the utilization of renewable power projects.

Previously, a policy published in October 2021 set a target of retrofitting 150GW of coal power plants during the 14FYP for the purpose of improving coal utilization efficiency, reducing coal consumption, and promoting clean energy consumption.

Many China climate experts have expressed concerns over the recent updates on coal in China. For example, Alex Wang, co-director of the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at UCLA, sees increasing coal profits as “bad news for climate action.”

He added: “Many signs point away from limiting coal. That’s not consistent with the peaking and neutrality goals. Why not stronger signals on clean energy? That would support energy security and development too.”

And he has a point. A recent paper shows that retrofitting coal power plants offer “marginal improvements” in renewable utilization, but that combining larger and regional balancing areas with dispersed renewables most reduces curtailment and coal use.

Coal position clarified

Interestingly, also this week, the National Energy Administration (NEA), released a batch of responses to the propositions submitted to the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CCCPC) during the “Two Sessions” last year.

One particular response on the “high-quality development of the coal power industry in light of carbon neutrality” caught the most attention. In this response, dated August 27, 2021, NEA confirms that coal power is an “important support” for peak power generation “under extreme conditions,” and that coal will maintain its “fundamental role” in China’s electricity structure for “a certain period.”

It added that China still needs to develop some “peaking units” for moderating variable renewable electricity, as well as some “supportive units” that secure grid safety on the premise of “strictly controlling coal power projects.” (Read my Twitter threads here and here for more context)

NEA also revealed that, during 14FYP, China will not build new coal power projects “solely for power generation,” but it doesn’t rule out the possibility of building “supportive units” of a “certain scale” that secure electricity supply and “regulatory units” that facilitate renewable energy consumption.

The energy administrator says the above “principle” would be included in the “14FYP on electricity development,” which has not yet been made public.

Curbing coal prices

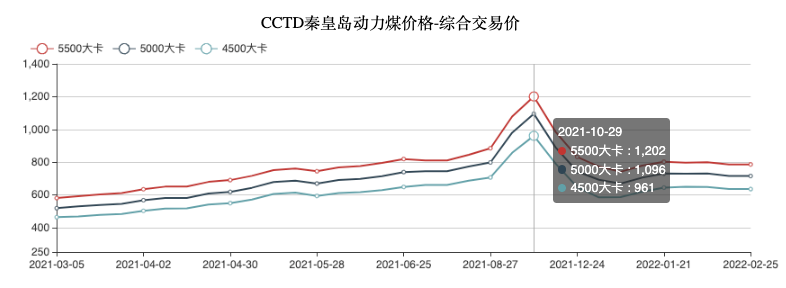

Also this week, the NRDC set a “relatively reasonable” price range of 570-770 yuan (US$90-122) for the medium- and long-term trading of 5,500 Kcal thermal coal (Kcal is an indicator of the coal’s energy content) at Qinhuangdao Port, the main hub of China’s north-to-south coal diversion, which also makes it the “world’s largest public coal terminal”.

The state planner also set separate price ranges for thermal coal produced in major coal bases. The benchmarks vary from 200-300 (US$32-47) to 370-570 (US$59-90), depending on the production area and the thermal value.

At the peak of the “energy crunch,” 5,500 Kcal thermal coal price surged to 1,202 yuan (US$190) — 60% higher than the higher end of the price range set by NDRC. (Credit: China Coal Transport & Distribution Association).

Analysts say the price difference for coal production and coal fuels is to “balance the profits” of coal miners and coal plants, and the range “mirrors” the coal power tariff reform, which allowed coal power tariffs to fluctuate higher, from 10-15% to 20%. It means power generators could transfer more cost to end-users in time of fuel price hike.

The new price benchmarks will take effect on May 1, 2022, and imported coal, which accounts for 10% of total consumption, will be exempted. NDRC says it aims to maintain a “smooth and stable” production, transport, and consumption of coal in the “intricate context” of the global energy market.

The state planner also encourages market players to link power tariffs with the coal trading price in medium-and-long-term electricity trading contracts to ensure an “effective transmission” of coal fuel prices to electricity tariffs. Analysts say this could help coal power plants “absorb surging coal prices.”

An NDRC official said in a press conference that the new mechanism sends a “clear signal” from the government, but that setting price benchmarks don’t mean going back to “government pricing.” Administrative intervention on coal and power prices within the “reasonable ranges” is strictly prohibited, he adds.

“Security,” Beijing repeats

The energy crunch has pushed “energy security” to the top of Beijing’s agenda, and this has implications for climate action.

This week, in the plenary session of the “leaders group” on peaking carbon emissions and achieving carbon neutrality (“shuang tan”), Han Zhen, Politburo Standing Committee member and vice-premier of China, repeatedly brought up “security.”

The meeting was held three days before the opening of the annual “Two Sessions.” Xinhua News captured the key messages of the meeting with a headline highlighting “a scientific rhythm,” “focusing on major and key [issues],” and “promoting [shuang tan] steadily and realistically.”

Han cited various “instructions” from Xi Jinping, China’s leader, including “coordinating development and security,” as well as key points from Xi’s most recent speech at the group study session of the Politburo on January 25 (I analyzed the speech here).

According to the read-out, Han heavily emphasized “security,” asking political leaders to “concurrently” ensure energy security, supply chain security, food security, and people’s livelihoods while reducing emissions.

In setting out the work priorities for 2022, Han noted the importance of “forming practical policy measures.” In particular, he asked for a clear accounting of coal demand and supply, as well as giving coal full play in the energy system as a fundamental energy source. He called coal the “last barrier” of energy security.

These messages are consistent with Xi Jinping’s address at the Central Economic Work Meeting held in December 2021. In that tone-setting meeting, Xi once more confirmed the “national condition” of coal being China’s “dominant energy source,” and instructed party leaders and governors to “ensure energy security,” highlighting the role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in securing supply and stabilizing prices. (See my line-by-line analysis of the meeting here).

They also echo one of the basic principles of China’s overarching guideline on energy transition — “adhere to [energy] security, and transform in an orderly manner.” The policy, jointly issued by NDRC and NEA in February 2022, is part of the “1+N” policy framework of China’s climate actions. (See my Twitter thread for more details.)

Importantly, the guidance says, the “orderly control and reduction of coal [consumption]” should come under the premise of “securing electricity supply.” It adds, “[we] should facilitate the transition of coal power to a source of “basic security” and “system regulation.”

With such a vision for coal, the state planner and energy administrator will set up a review mechanism for the retiring of coal-fired power units. According to the new policy, coal power units tasked with “supporting” and “security” roles can not be withdrawn from the operation without permission, and such units could be converted for emergency backup.

Canceled coal-to-chemical projects

At the same time, the dynamic in the coal-to-chemical industry is starkly different from coal mining or coal power.

As China continues to tighten environmental and energy requirements for energy-intensive industries, state-owned coal group Shanxi Coking decided to cease the construction of a large-scale coal-to-chemical project worth a cumulative investment of 2.5bn yuan (USD$396mn).

Unlike the Yulin coal-to-chemical project that was forced to halt construction in July 2021 due to incomplete preliminary procedures, Shanxi Coking’s decision was approved by the company’s board of directors as a response to the “macro policy and economic environment” having “significantly changed” since the project’s initial launch ten years ago. (More on the Yulin project here.)

According to the company notice, the integrated olefins, coking, and coal-to-methanol project, with a designed capacity of processing 60,000 tons of coal per year, was first registered in 2011 and received three separate permits from the provincial development and reform commission. It also completed other necessary preliminary studies and obtained relevant permits.

Still, after “full consideration” of factors like the “national and regional environmental policies” and the “tendency of overcapacity,” the company concludes that furthering the project would confront “major policy and market risks.”

To put this in context: Just a few days after the company’s announcement, NDRC released another guidance on energy efficiency, which requires energy-intensive industries to “basically wipe out” production capacities below the industry baseline before 2025. In particular, it aims to lift 30-50% of coal-to-chemical capacities to above industry “advanced levels.”

This is not the first time that the company has reacted to a more stringent environmental policy. Already in 2019, the company decided to end a coal-to-methanol project due to the “great difficulty” in meeting the control targets on coal consumption (“coal cap”) and pollutant discharge (“ pollutant cap”).

“It’s better to stop the bleeding in time than continue struggling,” an anonymous industry insider told the state-owned China Energy News. According to the newspaper, the coal-to-chemical industry is actively seeking new development paths, moving towards “high-end” and “high-quality” products such as coal-to-oil.

What’s at stake?

To be clear, I think it is important to acknowledge Beijing’s concern over energy security, which, for me, is a fair one. In the last two decades, China almost tripled its total energy consumption. With the economy still going strong, the pressure to secure energy supplies and stabilize energy prices — especially for fossil fuels, which still account for about 84% of its energy mix — is real and severe.

While the economic losses caused by 2021’s energy crunch are not yet clear, the social unrest that resulted from power rationing is much more straightforward. Earlier, award-winning environmentalist, Ma Jun, warned that mishandling the multiple challenges facing China could lead to social disruption and even “sacrificing the hard-earned progress on climate change.”

The main dispute is whether China should continue betting on coal for energy security. Subsequently, it involves debates such as whether coal power can fulfill its role as “basic security” and “last barrier” as Beijing anticipates, and whether the “supportive role” of coal power in facilitating renewable utilization is overlooked.

From the climate perspective, the concern is whether choosing such a path will undermine China’s energy transition, and consequently, its actions towards peaking emissions and reaching carbon neutrality.

Professor Wang Yi, an influential Chinese scientist and politician, has argued it is more important for China, a developing economy, to “not to reach the peak immediately but to move to a transition pathway that will lead to carbon neutrality in 40 years.” The question is, will current coal policies put China on such a pathway? (I strongly recommend anyone following China’s climate policy read my interview with Prof Wang at COP26 Glasgow.)

One thing is clear, China is on track to meet its key energy and climate targets for the 14FYP and its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) for 2030 — namely, “carbon intensity” and “energy intensity” per GDP — and it has the potential to do better. (For more context, read my analysis on China’s climate pledges under the Paris Agreement here.)

As statistics for 2021 show (see next section), even with record-high carbon emissions, energy consumption, and coal consumption, the intensity targets could still see a decrease as long as economic growth outpaces emissions or consumption.

For this reason, the total control targets on coal consumption (“coal cap”), energy consumption (“energy cap”), and carbon emissions (“emissions cap”) are much more important and instructive in terms of planning and progress assessment.

Entering the second year of the 14FYP, China still hasn’t issued the five-year targets for the above “caps.” In the absence of such rigid targets, it is sensible that Beijing’s “shifting political signs” on coal raise concerns among China climate watchers. Will the “Two Sessions,” starting tomorrow, provide us with more answers?

2021 Climate Statistics

This week, China published the Statistical Bulletin of National Economic and Social Development, and the China Climate Bulletin. The two bulletins include fresh data on China’s energy use and emissions, as well as the impacts of extreme weather events in China. Here are some highlights.

RECORD-HIGH EMISSIONS. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in China went up by 4% in 2021, rising 5.5% above pre-pandemic levels.

INTENSITY REDUCTION. Despite a surge in carbon emissions and energy consumption, economic growth outpaced energy and emissions in 2021. As a result, “carbon intensity” and “energy intensity” per GDP still went down by 3.8% and 2.7%, respectively, which put China on track to achieving its five-year targets.

MUCH MORE RENEWABLES. As of 2021, total renewable energy installation (including hydropower) reached 1,063GW, accounting for 44.8% of total installed power generation capacity. In total, renewable energy (including hydropower) generated nearly 30% of electricity in 2021, almost doubling the share of renewables in the electricity mix in 2007.

NUCLEAR BOOST. In 2021, nuclear power capacity totaled 53.26GW, a 6.8% increase from 2020. Nuclear plants generated 11.3% more power in 2021, accounting for 4.7% of total electricity production.

COAL’S SHARE DROPS. The share of coal in total energy consumption saw a slight decrease, dropping from 56.9% in 2020 to 56% in 2021. Meanwhile, the share of “clean energies,” a blanket concept that covers natural gas, hydroelectricity, nuclear power, and wind and solar power, reached 25.5%, an increase of 1.2 percentage points from 2020.

WARMEST IN SEVEN DECADES. The year 2021 marked the warmest year in China since the earliest available meteorological records from 1951. The national average temperature was 1.0°C higher than normal, and the frequency of regional high-temperature processes (two successive days above 35 °C) also doubled — both new records.

EXTREMER WEATHER. China in 2021 saw “more frequent and more extreme weather events that are widespread and concurrent,” including extreme rainfall events, cold waves, droughts, and sandstorms.

LOWER LOSSES. However, meteorological disasters caused “less” direct economic damage, such as crop damage, and less death of missing people, compared to the ten-year average, according to the Ministry of Emergency Management. The deputy director of the National Climate Center attributes this to an improved “capacity on disaster prevention and mitigation.”

The article is written by Hongqiao Liu and edited by Kevin Schoenmakers. It was firstly published in the "Shuang Tan" newsletter on 3 March 2022.