Interview with Zhuolan, an independent filmmaker, and some update about Shuang Tan 2.0

“Why hasn’t China gotten out of its coal obsession?”

“How did China roll out wind and solar projects at speed and scale?”

“Is China’s energy transition a just transition?”

“Do Chinese people, especially the youth, care about climate change?”

From closed-door consultations to public events, I often find myself grappling with these questions from my audience. As an analyst, consultant, and advisor, I usually structure my responses around factual evidence and rigorous analysis, drawing on relevant policies, scholarly articles, and survey findings.

However, there are moments when I feel drained from constantly wearing the analytical hat, and I begin to question the effectiveness of such communication. Having also experienced being a consumer of information, I’ve learned that sometimes, after thoroughly examining all the evidence and arguments, I crave to set rationality aside and just follow my gut feeling.

During my recovery from “creator burnout,” which unfortunately led me to suspend Shuang Tan after only a month of operation, I had the opportunity to reconnect with myself and the “China Watcher,” “climate Watcher,” and “China Climate Watcher” communities that I serve.

I gradually came to the realisation that the challenges we face go way beyond a mere lack of “China literacy,” “China intelligence,” or “China competence.” It is striking for me to conclude that, inside and outside of China, many people lack an empathetic lens to view Chinese society beyond politically charged narratives.

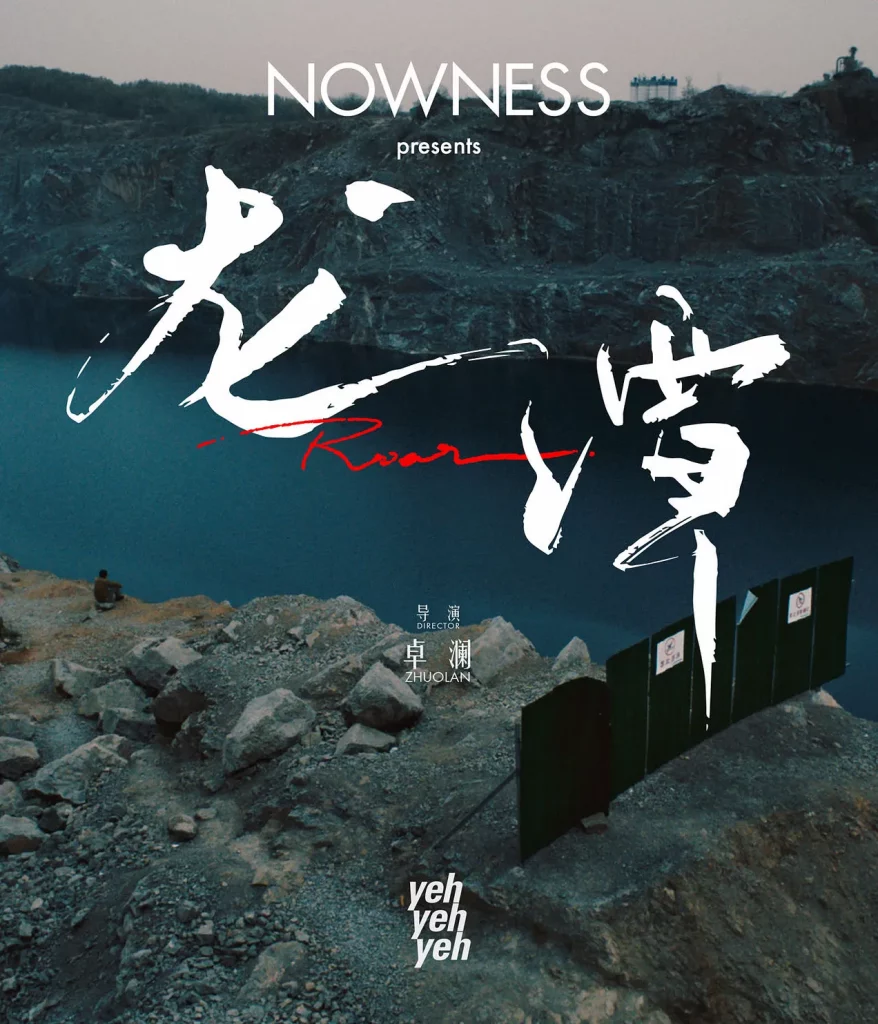

You can imagine how thrilled I was when I discovered “Roar” (《龙潭》), a short film directed by Zhuolan (ᠮᠥᠩᠬᠡ ᠵᠤᠯᠠ, 卓澜), a millennial Chinese independent filmmaker of Mongolian heritage. Her six-minute short film demonstrates that there are alternative ways to narrate China’s massive social, environmental, and energy transition.

Through her poetic lens, Zhuolan captures the essence of everyday life in Guqiao, Huainan, a small city in eastern China, and the “second life” of a decaying “city of coal” as a burgeoning solar energy hub following the disastrous legacy of land subsidence caused by decades of underground coal mining. (For more background on Guqiao, scroll down for “Extended Reading”)

Adding a touch of surrealism, the narrative takes shape through the perspectives of three local men and their fateful encounter with an invisible “dragon” that has been the guardian of the Central Plain (“中原”) for countless centuries.

Last week, I sat down with Zhuolan for a virtual coffee. We discussed her creative journey of directing “Roar”, her scientist-turned-filmmaker career, nature-influenced video storytelling, and, of course, the broader context of the short film — China’s challenging coal phase-out, fast-paced renewable roll-out, and how Chinese youth perceive climate change.

With her consent, I transcripted and translated our conversation to share with you in the newsletter.

Shuang Tan 2.0: A Brief Update

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to everyone who participated in the Reader Survey. I have carefully reviewed each survey response. Thank you for placing invaluable trust in me and the project. The survey is still open; complete it now!

After engaging in many fruitful virtual coffee sessions in the past few weeks, I decided to open a few additional slots for motivated readers. Hurry up, and book your FREE virtual session now!

I’m also happy to share with you that as I recover from “creator burnout,” I will gradually resume publishing, aiming for at least one monthly article before officially launching “Shuang Tan 2.0” on a due date.

During the transition period (“Shuang Tan 2.0 Beta”), I will test a wide range of writing styles, topics, and collaboration formats to:

- Determine the best methods for addressing the growing knowledge gap about China and its role in the climate crisis with my limited capacity and

- Find sustainable models to support this independent extracurricular project.

Scroll down to the end of the newsletter to see how you can support me on this journey.

This interview is the first attempt to provide readers with a more human-centred perspective on China’s energy transition, in contrast to the macro-policy interpretation and data analysis in Shuang Tan 1.0. (Read the Archive.)

Feel free to comment or reply to the email directly for feedback at contact@shuangtan.me. I am eager to hear from you.

Interview with Zhuolan: China’s Coal-to-Solar Transition through the Lens of a Millennial Filmmaker

Hongqiao: Congratulations on the success of “Roar.” Almost everyone in my energy and climate “bubble” has circulated it on their WeChat feed with praising comments. How did you decide to make a short film about coal and solar energy, and how did you set it in Guqiao, Anhui?

Zhuolan: First, I appreciate your kind words. I had no idea it received so much attention in the energy and climate communities!

To answer your question, the decision to make a short film about coal and solar energy stemmed from a commission I received from NOWNESS, a multilingual video channel that promotes creative storytelling, and yehyehyeh, a Shanghai-based consulting firm dedicated to sustainability, creativity, and innovation. After my previous short film, “In the Dusk,” won the NOWNESS Short Film Talent Award in 2021, they tasked me with directing a creative video on the topic of “energy”.

To begin the process, I researched extensively, scouring various sources ranging from TikTok to cable news. During this exploration, I stumbled upon the “photovoltaic lake” (“光伏湖”) in Guqiao, Anhui. This is an enormous water surface formed on the land subsidence area resulting from formerly underground coal mining activities. The young “lake”, which is only 10-15 years old, is now partly covered by floating solar photovoltaic panels. This discovery’s visual impact was so striking that I knew I had found the story I wanted to bring to life. The contrast between the two forms of energy and their respective impacts on the local community has thus become a central theme in the film.

Extended Reading

Guqiao coal mine, located in Guqiao Township, Fengtai County, Huainan City, Anhui Province, is one of the significant contributors to land subsidence issues in the region. Since its establishment in 2007, the underground mine, operated by Huainan Mining (Group) Co., Ltd, has been supplying coal to power plants in Huainan and Anhui Province. At its inception, the Guqiao coal mine boasted an impressive 10 million tonnes per annum (Mt/a) capacity, making it the largest underground coal mine in Asia at the time. However, mining activities have sparked conflicts with the local community, raised concerns about environmental pollution, and displaced over 13,000 Guqiao Township residents. In 2016, as part of the comprehensive management plan for the subsidence area in Guqiao and neighbouring counties, Huainan City initiated three floating solar photovoltaic (PV) projects with a combined installed capacity of 400 MW. The first 150 MW solar farm, invested by the Three Gorges New Energy Group, successfully connected to the grid in 2018, setting a new world record for floating solar PV projects.

Hongqiao: That’s intriguing. So, if I understand correctly, your initial intention was to focus on the “photovoltaic lake”. But when I watched the short film, I perceived it as primarily centred around coal mining and the impact of land subsidence on the miners, local industries, and the community. The “photovoltaic lake” was only lightly touched upon before the film ended with slightly exaggerated and surreal imagery. Could you explain the reason behind this approach?

Zhuolan: Before arriving in Guqiao, we had already conducted preliminary research on the land subsidence area. But once we set foot on the ground, I instinctively pointed the camera towards the subsidence area. It was almost a subconscious act driven by overwhelming emotional impact.

You may recall the scene of an abandoned house submerged in the lake. That image alone held immense expressive tension that words could not adequately convey. It evoked sadness, the passage of time, the convergence of history and the present, and even a hint of nostalgia.

Towards the end of the film, I used a drone to simulate the perspective of a dragon and added some special effects in post-production. During the shoot, I realised the story needed a non-human viewpoint.

My consideration was that most films on “energy” approached it from a human perspective, exploring the causes and consequences as they relate to human experiences. I want to introduce a novel perspective, one that examines how a “dragon,” a cultural and spiritual symbol of the Central Plain region, would perceive the changes unfolding in our world today.

Hongqiao: Since you brought up the “dragon,” I have two questions. First, why is the English title of the film “Roar” instead of “龙潭” (“Dragon Lake”), which is a direct translation of the Chinese title? Second, could you elaborate on its symbolism in the film? Does it represent Yan Huang Zisun (“炎黄子孙”), Chinese culture and society at large, or even the nation of China?

Zhuolan: Well, all three characters heard the faint roar of the dragon but didn’t see any. To me, the “dragon” symbolises all the unseen forces of nature. Interestingly, the “dragon” is a human creation rather than a natural one.

Growing up as a Mongolian ethnic in Inner Mongolia, “dragon” was relatively uncommon in my cultural heritage, where I was more familiar with Mongolian beliefs such as shamanism and Buddhism. But during my research, I discovered that the “dragon” holds much more significant cultural significance in the Central Plain, a traditional Han cultural region. So, as I sought a non-human perspective, incorporating the viewpoint of a dragon felt like a natural choice for the film.

Hongqiao: I really like the way you concluded the film. The three local men are initially seen standing on the PV panels. Then the perspective quickly shifts from a flat to a bird’s-eye view, or what you call a “dragon’s-eye view.” Observing the floating PVs from this vantage point created the impression of witnessing a massive art installation, with the human figures diminishing in size until they eventually disappeared from view, becoming insignificant like ants or specks of dust. Was there a particular message you intended to convey through this contrast?

Zhuolan: I believe you captured what I wanted to convey. As a filmmaker and a visual person, I was drawn to the aesthetics of floating PVs. Looking at them, I sensed a hint of a post-modern aesthetic. I vividly recall my reaction when I first stepped onto the floating PV panels. It was as if I were literally walking on water, with the soles of my shoes merely centimetres above the surface. And my immediate thought was, “This is not man-made. This is an alien base. It doesn’t belong to humans.”

It was an extraordinary sensation, almost divine. Not just me; the entire crew immediately fell silent when we stepped onto the floating PV panels. It was as if we all felt an otherworldly force. The vast expanse of water and sky and the profound silence seemed to erase the hardships and misery we had witnessed in the coal mines and land subsidence areas. I entered a meditative state, engulfed in the surrealness of the moment.

Hongqiao: I couldn’t help but notice that this short film focuses on the stories of three men, with very few scenes of female characters. This is somewhat understandable, as coal miners are predominantly male in the real world. But it’s quite a departure from your previous work, which primarily focused on women. Am I correct in observing this? Why is “Roar” an exception?

Zhuolan: That’s true. When I initially conceived the film, I envisioned it to revolve around the stories of three men. This is mainly because coal, or fossil energy in general, has always evoked imagery and emotions such as darkness, heaviness, and a lack of tenderness, love, and hope. Words like “structure,” “systems,” and the tension between humans and nature were at the forefront of my mind. Additionally, the striking visuals captured in the film, particularly the abandoned industrial sites, leave little room for delicate emotions, which I usually express through female characters.

Hongqiao: I also noticed that the three actors were cast using their names. Are their stories based on reality? Does this imply that the film has a documentary approach and that you captured their actual lives on film?

Zhuolan: Sure, except for the special effects at the end, we approached the rest of the footage from a documentary perspective. For instance, I didn’t give the first male character, a middle-aged mine worker, extensive direction because I wanted his performance to feel as natural as possible. In a scene where he craves stones, I told him to carve something — anything, really. I didn’t delve into what he carved or how he carved it.

On the other hand, I encountered the second man while filming the lake with a drone. In the drone footage, I noticed a man rowing a tiny boat, so I followed him as he moved from the house in the water to the shore. He had a perfect connection with the water and exuded a captivating American cowboy spirit that I admired.

The third man, a teenage dragon dance performer, is also a member of the local College of Physical Education’s dragon dance team. I depicted him as a “dragon heir,” symbolising youth and connecting us to the future.

However, it’s important to note that what we presented in the film is only a subset of reality. The city is not as desolate as it may appear; mines have been abandoned, factories have closed down, and villages have been relocated, but life continues.

Hongqiao: I’d like to revisit a keyword you mentioned earlier: “emotional impact.” Could you elaborate on what you experienced?

Zhuolan: The emotional impact I had was quite complex. Firstly, there was a profound visual impact. Guqiao was nothing like any of the rural or urban landscapes that I was used to. The environmental degradation caused by coal mining and the surrealism that emerged from the photovoltaic lake, both as a result of human intervention, forced me to rethink the relationship between humans and nature.

There was also a disconnect between my outsider perspective on what coal mines and land subsidence meant for the local community and the mentality of those who are actually living with the consequences.

As an outside observer, I arrived in Guqiao wondering, “Why didn’t things work out here?” Due to land subsidence, mines and factories were forced to shut down, and workers, many in their 30s and 40s, faced early retirement. How did they handle such circumstances? They formed a collective, engaging in group physical exercises and dragon dancing. They exhibited incredible resilience and even a glimmer of hope and optimism, which caught me off guard.

Hongqiao: Since I first read about it from the WeChat feed of a climate philanthropist, I assumed that you were sponsored by climate foundations and collaborated with non-profit organisations aiming to raise awareness about the energy transition. But, as you explained, this was a purely commercial project. I am curious: Did you coincidentally incorporate the most heatedly debated topics in the climate sphere (e.g., coal phase-out, renewable energy expansion, and just transition) all at once?

Zhuolan: Actually, prior to our conversation, I had never heard of the term “just transition.”

I’m not the type of creator who enjoys lecturing the audience. I didn’t approach filmmaking with the mindset of “I have something very important; listen to me now!” Sensationalism isn’t my cup of tea, either. In truth, I prefer maintaining some distance between myself, the audience, and the subject matter.

However, if I were to convey a message, it would be expressing what was on my mind: “Something is evidently wrong, and this makes me uncomfortable. We should do something about it.”

Hongqiao: We’ve been referring to “Roar” as a “short film.” But compared to the typical definition of short films, which can range from 15 to 40 minutes, it’s more akin to a “micro film.” What led to the decision regarding its length? Would you contemplate developing a longer film based on the same topic, delving deeper into the lives of the three men rather than merely presenting a snapshot?

Zhuolan: It’s worth repeating that the film wasn’t created to further a specific public agenda, nor was it intended as a public service. It was conceived and implemented as a commercial project. Consequently, the film shouldn’t exceed 6 to 7 minutes, which, to my understanding, is likely the maximum duration the Chinese audience can bear for online content nowadays.

On the one hand, it’s regrettable that I must infuse a hint of commercial appeal into my creation to survive in today’s Chinese media market. Otherwise, it won’t attract investors or captivate the audience. However, I believe there are still opportunities to explore the intersection of art, fashion, and energy or climate. In this regard, yehyehyeh has demonstrated great vision in supporting me with a project like this, which may not yield immediate returns.

In response to your second question, I am not ready to develop a longer film on this topic yet, but I would be thrilled to revisit Guqiao in four or five years and reconnect with the person I am at present. I hope I will be able to take another look at coal, renewable energy, and the notion of “just transition.”

Hongqiao: What kind of response have you received so far since it was released at the end of April?

Zhuolan: Most attendees at our live events expressed more interest in the production details than energy and climate issues.

A scholar, however, mentioned something I couldn’t stop thinking about during the premiere event. He stated that renewable energy must account for 70% of China’s electricity production by 2050 to meet China’s “Shuang Tan” (“双碳”) targets.

I knew China was undergoing a significant energy transition, yet I was still surprised by the pace at which it was happening. Solar PV is still a relatively new creation to me, and I can’t help but wonder how such rapid growth can be achieved when many challenges and obstacles surrounding renewable energy remain unresolved. My mind is filled with questions!

Hongqiao: Do subjects like nature, energy, and climate change come up often in your daily life? Nature seems to play a significant role in all of your short films.

Zhuolan: Indeed, these topics are pretty familiar to me. I was born and raised in Inner Mongolia, where we can access nature’s wonders directly. As a child, I spent nearly every weekend frolicking in the meadows, and family discussions often revolved around nature and wildlife. Many family friends also worked in sandstorm remediation and open-cast coal mining. Furthermore, during my undergraduate studies in marine geology, I focused my thesis on the carbon cycles in the Okinawa Trough of the East China Sea. So, climate change has always been on my radar.

But I didn’t pursue a career in filmmaking to escape the realm of science. On the contrary, I entered the world of cinema because I realised that science alone wouldn’t enact the necessary changes. We need to establish more dialogue between the scientific community and the broader society, and films serve as a beautiful medium to facilitate such discussions.

Hongqiao: What about your friends? Are they concerned about climate change? You were born in 1994, placing you towards the tail end of the Millennial generation…

Zhuolan: To be honest, I feel my friends and acquaintances aren’t particularly concerned about climate change. It’s not a topic that frequently arises in our conversations. Naturally, they will watch my film when it is released, but beyond that, energy or climate change doesn’t feature prominently in their lives. This unfortunate situation somewhat explains why yehyehyeh and I connected so effortlessly. The agency is committed to all sustainability matters, including climate change, and I am likely one of the few Chinese filmmakers who remain drawn to this subject.

Hongqiao: Why do you think climate change, as you just described it, is an unpopular topic among your friends?

Zhuolan: Generally speaking, there is a widespread perception that environmental and climate issues are distant from people’s day-to-day lives.

Ironically, though, brands and filmmakers often enjoy travelling to picturesque mountains to shoot their commercial films. Yet, their interest often extends no further than the aesthetic beauty provided by the natural landscapes and the associated bourgeois lifestyle. You must have seen those commercials featuring wool sweaters on the prairie or hiking gear in snowy mountains…

But I won’t say that nobody cares about climate change. I am sure some people are highly concerned and are taking serious action. It’s just that we still have a long way to go in terms of popularising climate action.

Hongqiao: Is it because it seems too abstract, or are there simply too many other everyday struggles to contend with?

Zhuolan: Both factors come into play. The challenge is that the average Chinese person only encounters climate change as an issue in the context of national policies or government campaign slogans. Even if people want to take action, many are unsure where to begin. Does reducing the use of plastic bags make a positive difference? Should we minimise takeaway containers and eat more meals at home? We lack practical guidance.

But I’m not permissive. I am positive that Chinese youth are willing to adjust their consumption patterns and lifestyle habits when directly confronted with the threats arising from climate change.

Hongqiao: Hmm, you raise an interesting point. Perhaps I spend too much time within the “green bubble” and have lost touch with the general public…

Zhuolan: Ha! Maybe being “green” isn’t cool enough at the moment. If you look at our generation of young people, most of them still lead lifestyles heavily influenced by capitalism, and many are, in fact, trapped by consumerism. When environmentalism and a low-carbon lifestyle become a fashion, more and more individuals will join in.

About Zhuolan

Zhuolan (ᠮᠥᠩᠬᠡ ᠵᠤᠯᠠ, 卓澜) is an independent film director from Inner Mongolia, China.

Growing up in a Mongolian family, she has a deep passion for nature and its connection with human beings, especially in how people’s affection and emotions are implicitly yet greatly formed and influenced by nature. That is the locus that binds her natural science and cinema pursuits.

As a film director, Zhuolan wants to dedicate her work to presenting more stories of people of different identities in East Asia to the world. Besides her interest in visual storytelling, she is also fascinated by the sound of nature, the soundscape of breezes and waves, human sensual eulogies, and dance steps, and this can probably explain her 4 years of being a local rock n roll band vocalist.

Zhuolan holds a B.S. in Oceanography from Tongji University and earned an M.A. in Cinema Studies from NYU Tisch.

Can’t wait to read the weekly in-depth coverage from Shuang Tan 2.0?

There are several ways to support my independent extracurricular work:

👍 Like and share the newsletter with your social network

☕ Buy me a coffee – or several cups!

💱 Consider a paid subscription pledge

🤑 Connect me with potential donors or investors*

📋 Write for Shuang Tan**

📝 Complete the Reader Survey

🙌 Write a testimonial

You know how to reach me: contact@shuangtan.me.

Till next time!

Hongqiao

* With the premise of maintaining editorial independence, Shuang Tan accepts public and private funding that runs beyond six months.

** You are encouraged to pitch a story on an overlooked, less or misunderstood issue in the intersection of #China and #climate. Contributions to Shuang Tan are not compensated at the moment, but you can leverage the platform to convey your voice directly to the inboxes of 1,300+ China Watchers and Climate Watchers in over 70 countries.

The article is written by Hongqiao Liu. It was first published in the "Shuang Tan" newsletter on 22 May 2023.